Life's most important problems

Richard Hamming's question applied to the life sciences

tl;dr – Increasing the number of healthy years in people’s lives is one of the few endeavours that may benefit the world for generations to come. Inventing medicines is the highest leverage approach to create more healthy years. The three most important challenges to inventing more medicines are (1) discovering new targets, (2) solving delivery of medicines to the right cells, and (3) increasing the number of human data points we collect. Each of these problems has the potential for tremendous positive impact.

Richard Hamming famously posed a deep question to his colleagues at Bell Labs:

What are the biggest problems in your field? Why aren’t you working on them?1

One can apply Hamming’s question recursively at increasing layers of resolution. What are the most important goals for humankind? What are the most important fields working toward those goals? What are the most important problems in that field?

Why aren’t you working on them?

Here, I outline one such orbit that led me to my own field of therapeutics development, and the key problems that stand between us and inventing an order-of-magnitude more medicines.

Quests of import

Few human endeavours have an impact that persists beyond the scale of a single lifetime2. Progress in science and technology – the accumulation of useful knowledge – is one of the only forces that compounds and enriches human life on the scale of centuries3.

What are the most important scientific & technology problems in our era?

Making energy too cheap to meter4

Expanding the footprint of humankind beyond a single planet

Creating abundant, capable intelligence

Increasing the number of happy, healthy years in each human life

There are reasonable arguments for other endeavours to be included on this list, but even this small set captures a large swath of the worthwhile goals.

Creating more healthy time for each individual is perhaps the ultimate goal among these. Even if our species reaches a technological velocity that provides material abundance and the Von Neumann probes are replicating prodigiously among Dyson spheres near each proximal star, each of us will want to live to see it.

Increasing the number of years we have to pursue fulfilling experience and spend with one another will remain the most valuable possible product. Health is an endless frontier.

Health production function

What are the most important problems in the life sciences? How do we create more health?

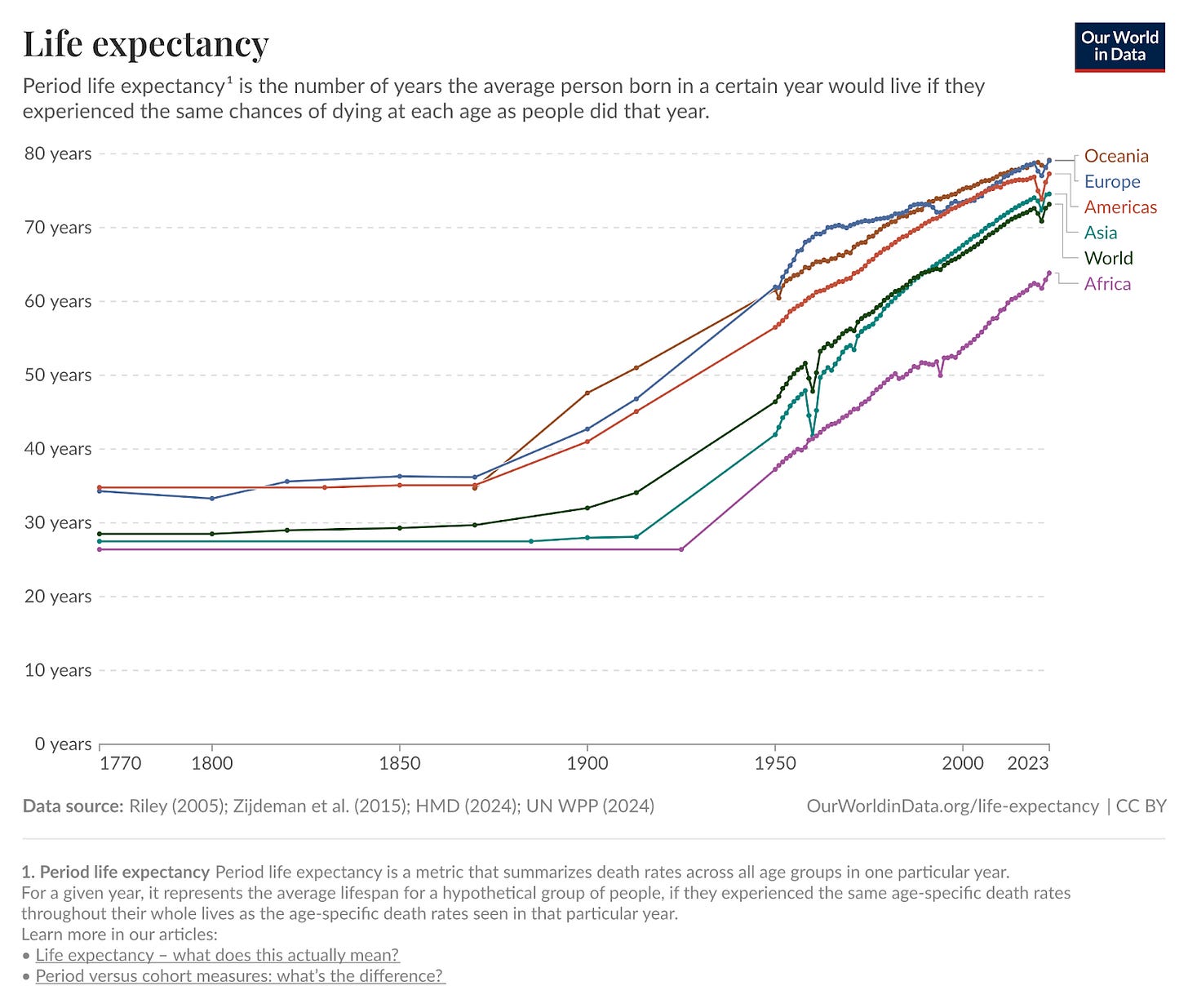

Our health is roughly the product of (1) the technologies we have to prevent and treat disease in the form of medicines, diagnostics, devices, and sanitation programs and (2) the distribution of these technologies through a healthcare system. If health technology is the dominant variable in the equation, we would expect trends in health and life expectancy to be similar across geographies, despite differing health care systems. We might also expect trends to be monotonic because medicinal technology rarely reverts over time.

By contrast, if distribution is the dominant variable, we might expect that some geographies sharply diverge as a function of superior healthcare systems. We might also expect that these trends are volatile and non-monotonic, improving and declining as the political winds and fiscal vitality shift within a polity.

The data strongly support the notion that therapeutic technology is the dominant factor that determines our health. Life expectancies have increased almost monotonically for the past century5, and this trend is constant across geographies. Despite the dramatically different levels of wealth across the globe, the low marginal cost and rapid diffusion rate of therapeutic technology means that much of the world’s population can benefit from new medicines.

Even the least wealthy geographies are experiencing the same upward trend of progress. The average lifespan worldwide today is nearly a decade longer than the average lifespan of the wealthiest geography in 1950.

Distribution of these technologies is of course an important variable. Therapeutic technology sets the maximum health we can achieve, while distribution sets the minimum.

One way we might further quantify the impact of technology vs. distribution improvements is based on the expected gain in the number of healthy years we might achieve from each. The lifespan gap across geographies due to distribution is on the order of 1 decade. The lifespan gap between the healthiest humans who live to 1106 and the median in the wealthiest geography is 3-4 decades. Most of our latent potential health requires technological improvements to unlock.

Inventing medicines is therefore the most impactful way to increase the number of happy, healthy years in the average human life.

Therapeutic Hamming problems

What are the most important problems in the field of therapeutics? What prevents us from creating new medicines?

I’ll argue that there are three problems with outlier impact.

Discovering new therapeutic “targets”

Delivering therapies to specific cells & tissues in the body

Evaluating more therapeutic hypotheses in humans

Target discovery is critical because in the vast majority of circumstances, we simply don’t know what biological manipulations will be sufficient to preserve health in a human patient. All problems of therapeutic engineering and evaluation are secondary to this fundamental epistemic challenge.

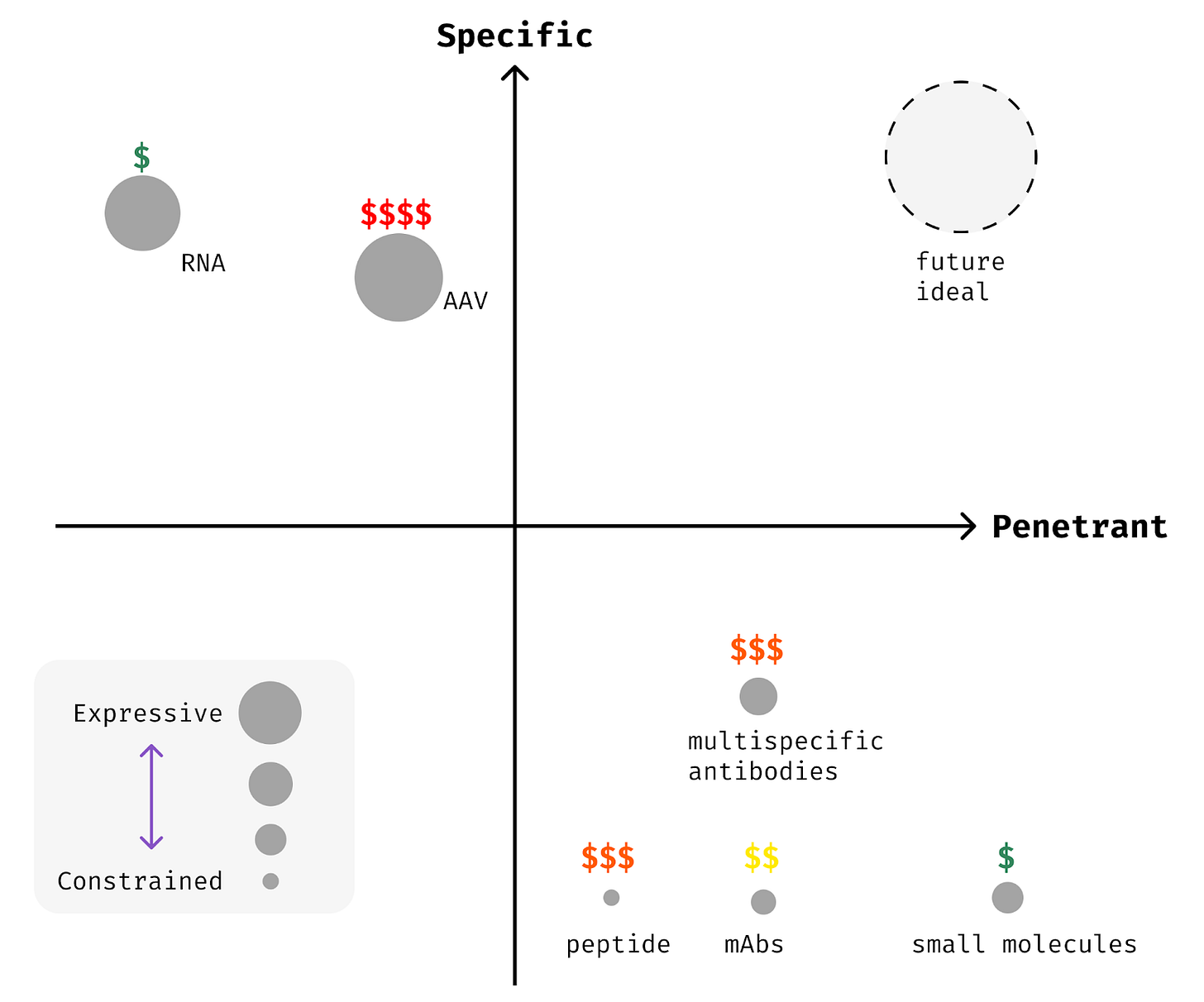

Once targets are known, the largest challenge in building a therapy is delivering a medicine that is sufficiently expressive to the right cells and tissues. Today, our therapeutic approaches each make harsh trade-offs between the axes of penetrance (how many cells are affected), specificity (how many of the right cells vs. the wrong cells), and expressivity (how sophisticated the effect is within the target cells).

Ultimately, both target hypotheses and therapeutic designs must be evaluated for their effect on human health. Our existing preclinical systems (e.g. animal models) suffer from poor predictive validity. What works in these systems rarely works in humans! In order to invent more medicines, we need to collect more data in humans directly. These data will let us both improve our preclinical systems, and test more hypotheses in the most relevant settings.

Others might argue that (1) improving preclinical predictive validity directly, absent more human data, (2) reducing regulatory overhead and development costs, or (3) changing intellectual property and reimbursement incentives are more critical. While there is a case to be made for each of these notions, I think the arguments for our three problems above are far stronger.

Target discovery

Previously, I’ve discussed the target discovery problem at length (see: Creating therapeutic abundance). I believe it’s the most important problem in therapeutics. I’ll refer to this previous post for an in depth treatment of the topic.

tl;dr – The invention of new medicines is rate limited by our knowledge of cells and molecules (”targets”) that we can manipulate to treat disease. The cost of discovering new medicines has increased because the lowest hanging fruit has been picked on the tree of ideas. Emerging technologies at the intersection of artificial intelligence & genomics have the potential to unlock a new era of target abundance, potentially reversing the decades-long decline in R&D productivity. If realized, this will be one of the most important impacts of AI over the coming decades.

At an even more granular resolution, we might ask “What therapeutic targets are the most valuable to discover?” The trivial answer is that the most valuable targets are those that provide the most additional health, for the most people. In practice, this reduces to discovering target biologies for the pathologies of aging that affect every person on the planet.

Effective delivery

Once target biologies are discovered, we need to deliver medicines to the right cells and tissues within the body. This involves building medicines that are penetrant, specific, and expressive.

Penetrant medicines can reach a broad set of cells and tissues. Specific medicines can act primarily on the cells and tissues of interest while avoiding activity elsewhere. Expressive medicines can encode complex logic and interventions, while less expressive, “constrained,” medicines are restricted to blunt modifications. An expressive medicine might activate many genes if and only if a disease-associated gene is also expressed, whereas a constrained medicine might simply deactivate a single gene everywhere at once. Most of the medicines we have today are of the constrained variety.

Penetrance is self-evidently important. If a medicine can’t reach the right cells and tissues, it can’t exert a therapeutic effect! Specificity is critical as well to unlock many therapeutic targets. Biology reuses the same critical molecules across various contexts in the body, so that genes might be more akin to letters or words than sentences in their semantic content [6]. Imagine trying to change the meaning of a book if your only edits were to delete every instance of a given letter. It might be possible, but challenging. Non-specific medicines are a similarly blunt instrument. Specifically acting upon a gene or cell type within a given tissue is much more powerful.

Today, our ability to build medicines that are both penetrant and specific is quite poor. Our ability to create expressive therapeutics is even more limited.

Traditional therapeutic modalities like small molecules, antibodies, and proteins are wonderfully penetrant. They can reach most tissues readily, with a few exceptions like the central nervous system. However, they are mostly non-specific, acting upon their targets across the body without much control. This means that a number of otherwise strong therapeutic targets can’t be drugged effectively with these traditional methods.

Emerging modalities like nucleic acid therapies (RNA and DNA medicines) can often be made specific, but they are rarely penetrant. Most nucleic acid medicines can be delivered only to a handful of cells and tissues today. Addressable cell types for RNA medicines are limited to those where modified RNAs or lipid vehicles like LNPs can travel. Canonically, the liver is the easiest place to target because it’s biologically optimized to filter these types of particles from your circulation. Immune cells and endothelial cells lining your veins and arteries can be targeted with a bit more effort.

The vast majority of our existing medicines are constrained, inhibiting or activating a single molecule or gene without logical gating. Almost all small molecules, protein biologics, and RNA therapies fall into this category. Only recently have the earliest glimpses of expressivity been realized in patients. Multi-specific biologics, combinatorial RNA medicines, and logic-gated cell therapies are now emerging. Nonetheless, we are far from building medicines that match the complexity of the pathologies we hope to treat.

Evaluating hypotheses in humans

The final step in any therapeutic development process is placing a medicine into human patients and measuring if it works. All of the prior steps – in silico simulations, cell culture models, animal studies – are attempting to predict the outcome of this human trial.

All of preclinical development is then a binary classifier implemented with atoms to predict the success or failure of clinical studies. Even clinical studies are binary classifiers to predict success in the real world! Despite this obvious truth, we rarely frame the problem in this fashion or even explicitly measure how well our preclinical systems predict what happens in patients.

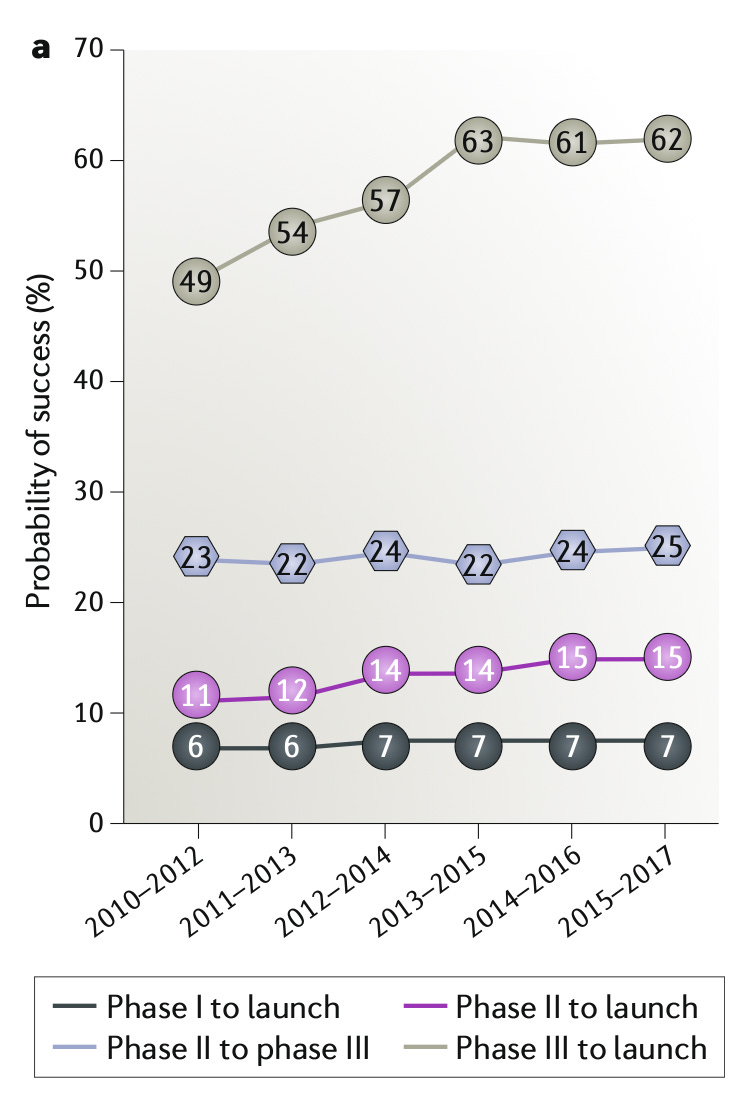

Unfortunately, we do know that their performance in aggregate is wanting. ~90% of therapies fail in clinical trials, despite presumably strong ex ante preclinical data. This general phenomenon has been described as a crisis of “predictive validity,” by Jack Scannell and others [Scannell 2022].

Given the poor performance of preclinical models, the value of additional data in humans is tremendous. These measurements can be used not only to directly determine which medicines work, but also to improve our preclinical systems, allowing the returns to compound over time. We can’t hope to improve the predictive validity of our preclinical systems if we don’t even have enough data to measure our performance. Gathering more human data is therefore one of the most important problems in therapeutics.

By the numbers today, our species tests ~3,000 new therapies in humans per year7. Statistically, only ~50% of the new medicines tested in initial safety trials (Phase 1) will succeed and progress to efficacy. This means that only ~1,500 new medicines are tested for efficacy in a given year across all geographies and diseases. There are thousands of recognized pathologies (“indications”) by the US FDA, so we’re effectively testing <1 medicine/pathology/year for efficacy.

It’s difficult for us to improve either our systems of discovery or the absolute number of therapies available given this tight constraint. There are in principle three ways we might collect more human data points:

Increasing the number of clinical trials – run more trials of the same form that dominate today

Decreasing patients/trial – run smaller trials to test more drugs for similar cost

Increasing the number of agents/patient – test more than one medicine per patient

There is a tremendous focus in the industry on increasing the number of trials by cutting costs. Capital is often the limiting reagent for human data generation because most R&D spending occurs in the clinic [Sertkaya 2024]. However, this approach will hit a scaling limit based on other inputs. Clinical trials require not only capital, but patients, clinical centers, and manufacturing capacity8. If there aren’t enough patients to enroll, the marginal cost of a trial isn’t the bottleneck.

We can likely increase the number of clinical trials by 2X through naïve scaling and cost efficiencies, but it seems unlikely we’ll increase by 10X using this approach alone.

Reducing the number of patients per trial would not be beneficial if this resulted in underpowered studies. Rather, technology may enable us to preserve the same statistical power with smaller cohorts. New measurement technologies may allow us to select patients for trials more effectively and provide new endpoints that enable shorter, smaller trials.

As a synoptic example, heart disease trials using a newer biomarker (LDL-C) endpoint are ~10-100X smaller than those using the traditional all cause mortality (“death rate”) endpoint9. If technology can provide superior endpoints for other indications with similar predictive validity, trials become far more scalable.

Least explored among these options is the notion of testing multiple therapeutic agents per patient. In discovery research, pooled screening experiments are often conducted that deliver different perturbations to each cell in the body of an animal. This allows researchers to measure the cell-autonomous effect of many potential therapeutics simultaneously in the same organism10.

As shocking as it may sound, similar studies have already occurred in humans. Lentiviral-based CAR-T cell therapy involves the random integration of a transgenic cassette across millions of sites in the human genome, so each patient in essence receives a mixture of millions of distinct therapies [Biasco 2021]. More directly, CAR- & TCR-T trials have been run where a series of gene edits are introduced at varying efficiencies <100%. The resulting pool of cells then contains all possible combinations of the edits at some frequency [Stadtmauer 2020]. Each cell is challenged to respond to the cancer and grows as a result, so whichever combination of these distinct cell products is most effective has a chance to benefit the patient.

In each of these studies, many assets were effectively tested simultaneously in a single patient.

Cell therapies are a special case where cells are the obvious unit of replication. Nucleic acid medicines like RNA and gene therapies may represent a similar setting. Measuring the effect of multiple small molecules or antibodies in a patient is more challenging because these medicines have systemic effects that can’t be disentangled. There are nonetheless nonclinical settings where pooled screens can be performed in human-like systems regardless of modality [Arap 2002]. Leveraging these approaches could generate as many human data points in a single trial as our entire species generates in a full year, albeit at the cost of less information per asset.

All three of these mechanisms to increase the number of human data points we collect are likely needed. New technology has a role to play in each. I look forward to outlining more thoughts about how to tackle these challenges in a future post.

Coda

We experience but one life. Exceedingly few of our actions will have an impact on the scale of generations, even fewer on the scale of centuries. It’s a gift to contribute toward a goal that will benefit those who follow long after us.

Providing each person with more happy, healthy years is among those rare goals. The beauty of our modern therapeutics industry is that we can awake each day knowing that success is worthwhile, if arduous to achieve.

Medicines are perhaps humankind’s most advanced creations to date. The scientific challenges involved are so great, it’s a wonder that we’ve invented any therapies at all. A few of these challenges – discovering new targets, delivering medicines to the right cells, and measuring the effects in humans – offer an opportunity for impact worth the efforts of a lifetime.

What are the biggest problems in your field? Why aren’t you working on them?

Thanks

Thank you to Stephen Malina, Alex Telford, and Jacob Trefethen for reading a draft of this post and substantially improving the logic.

From Richard Hamming’s lecture “You and your research”

The Assyrian kings once reigned over an appreciable fraction of the world’s population, yet today they are known only from the remnants of a distant provincial library that survived the fall (The Story of Civilization, Our Oriental Heritage by Will Durant). Byzantium’s greatest financiers are known only by the mechanical residues of the account books. The average American cannot name the full sequence of United States Presidents from even 1950 until today.

See Joel Mokyr’s book Lever of Riches for a persuasive case in this regard.

To first order, the amount of energy produced & consumed by a civilization is a reasonable proxy for their wealth and well-being: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kardashev_scale

Life expectancy improvements are not entirely monotonic. Most notably, there is a decrease in 2019-2020 as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even this fluctuation further supports the hypothesis that technology is the dominant determinant of health. Even the richest geographies experienced profound suffering from the pandemic. No amount of financial resources can save a polity from disease if the technology simply does not yet exist.

There are hundreds to thousands of individuals with confirmed life spans >=110 years.

Estimating the true number of unique medicines is tricky. There isn’t a trivial way to deduplicate trials across geographies, and some “new molecular entities,” represent very minor variations on existing therapies. Here, I’m basing an estimate on the number of new molecular entity applications to regulators, then estimating the rate of duplication. US FDA processes ~1,500-2,000 INDs [Lapteva 2016, US FDA CBER metrics, US FDA CDER metrics, combined US FDA metrics], the Chinese NMPA processed ~2,500 new entities in 2024, and the EU EMA doesn’t report IND-like processing legibly, but best guesses put the number in the 100s at most. The majority of Chinese new entities were distinct from the US FDA (69%), so we estimate the total number of new entities at <3,500.

Clinical trial enrollment is often limited by the number of available patients. As just a few examples: Inflammatory bowel disease trial recruitment has slowed by >5X over the past 25 years due to improving standard of care and a competitive trial landscape [Sharp 2020]. Improved standard of care and competition have made trials for ATTR more challenging [Fontana 2025]. MASH trials have to screen increasing numbers of patients to enroll as the number of trials expands and screen failure rate (a proxy for initial recruitment quality) increases [Souza 2025].

For example, the trial measuring LDL-C reduction for evolocumab (anti-PCSK9 antibody) enrolled 614 patients and ran for 3 months/patient [Koren 2014]. The subsequent all cause mortality study enrolled 27,564 patients and ran for a median of 2.2 years/patient [Sabatine 2017].

See [Jensen & Marblestone 2021, Saunders 2025] for examples. We also run in vivo pooled screens in humanized liver models at NewLimit.

This is such a crisp application of Hamming’s question to therapeutics, and I appreciate how you resist the usual hand-wavy “longevity” framing by naming three concrete bottlenecks: target discovery, cell-/tissue-specific delivery, and the scarcity of high-quality human datapoints for hypothesis testing. The part that lands hardest is the human-data constraint: preclinical work can be elegant and still systematically miscalibrated, so the fastest path to more real medicines is often better measurement + trial design (adaptive/platform trials, better intermediate endpoints, more pragmatic enrollment, and tighter integration of real-world data) rather than ever-more-perfect mouse models. And on delivery: your “penetrance–specificity–expressivity” triangle is a helpful mental model for why so many “obvious” targets stay undruggable in practice. The most hopeful subtext here is also the most demanding: if we want an order-of-magnitude more medicines, we’ll need to treat clinical research infrastructure (and patient trust/participation) as a core technology; something we intentionally build, standardize, and make accessible, not an afterthought.

I read your post with interest. In addition to your list of "What are the most important problems in the field of therapeutics? What prevents us from creating new medicines", I might add the following:

Disease origination: What fundamental biologic components might initiate and determine specific disease expression?