Inventing the NIH

This post began as a book review of Inventing the NIH by Victoria Angela Harden, but grew out a bit from there.

How did the US create one of the most impactful scientific institutions in history?

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s pre-eminent biomedical research agency. The annual NIH budget ($40B+) is an order of magnitude larger than peer institutions (CIHR in Canada, MRC in the UK) in nominal terms, and commensurately the NIH is responsible either directly or indirectly for a plurality of the world’s impactful biomedical research each year.

One reductive but instructive data point on the impact of the NIH is the number of Nobel Prize recipients with NIH funding. NIH-funded scientists have received >10% of all Nobel prizes in history. If we subset to the Nobel Prizes for Physiology and Medicine (110 total prizes) or Chemistry (111 prizes) where all but two NIH-funded scientists received their awards, NIH-funded scientists have received a shocking 42% of all prizes. This is especially notable given that the NIH has only existed since 1930 and the Nobel’s began in 1901.

In just the 2010-2016 period, NIH funding can be traced to scientific breakthroughs that supported the development of 210 new drugs. (It’s important to note that NIH funded basic discovery is but one component of the vexing, arduous path to drug discovery.)

From even a cursory glance, it’s apparent that the NIH is responsible for a non-trivial fraction of human progress in both biology and medicine. I’ve long been fascinated by the NIH as an institution: how did it come to be; how does it prioritize abstract, long-term goals; and how might we improve the funding mechanisms of the NIH to accelerate biological discovery.

Given that the NIH funds such a large portion of discovery in one of the most rapidly advancing scientific fields, it seems that we can learn a great deal about scientific progress by investigating the NIH’s political origins and operational decisions.

It strikes me that the NIH’s mandate is much more radical than most presentations of the institutions long history suggest. The NIH fundamentally takes taxpayer dollars, bequeathed by all, and uses that revenue to fund exploratory, high risk basic research. In the language of venture capital, the NIH is black swan farming, but rather than risking the funds of wealthy limited partners, the NIH invests with the public purse.

I believe this arrangement has led to almost unquantifiable good for humanity, but nonetheless, it’s a shocking proposition to include in a political speech.

Imagine the pitch:

“I would like to take tax dollars, disperse them widely on a number of individuals with interesting but inherently difficult to justify ideas, and then we’ll cross our fingers and hope for the best.”

But the pitch worked!

And so did the science!

How did this happen?

Inventing the NIH — A Review

Victoria Harding presents a step-by-step account of the NIH’s political origins in Inventing the NIH, with a strong focus on the role of non-governmental organizations and lobbying groups. She eloquently outlines how the NIH blossomed from much smaller beginnings into a high-growth scientific juggernaut. While insightful, Harding’s text is written for the academic historian and a bit difficult to consume for leisure. I’ve tried to extract some of the main insights below in a briefer form.

The Marine Hospital Service and the Hygiene Laboratory

The NIH was not created anew from whole-cloth in a single legislative text. Rather, it was built upon existing institutional foundations, created for related but distinct purposes.

The deepest origins of the NIH connect back to the Marine Hospital Service, a network of hospitals specifically created to treat ill seamen, funded by a tax on their wages. In a way, we can think of this network as a form of integrated health insurance similar to Kaiser Permanente in modern California. The Service was originally run within the precursor to the US Coast Guard, but was given independent management after the Civil War within the Department of Treasury. This change in management led to the development of distinct class of public health civil servants within Hospital Service.

Crises and external circumstances began to expand the Hospital Service’s initial mission. Beginning with management of quarantines for incoming ships, Congress and the executive branch began asking the Hospital Service to manage and investigate various other public health problems.

It seems like the logic here was roughly: Who has the personnel to deal with problem X? That weird marine worker insurance program? Sure, give it to them.

Germ theory developed in the late nineteenth century, representing one of the great conceptual advances in modern biology. As part of the growing list of demands from Congress, the Hospital Service came to employ a few students of this new doctrine, including a direct trainee of Robert Koch himself, Joseph Kinyoun. Kinyoun was placed in charge of establishing what we would now recognize as a basic research facility, termed the Hygienic Laboratory in keeping with the nomenclature of the time. This laboratory was fairly small by modern standards (< 200 employees), but it was the first time federal funding was used to support ongoing basic health research.

Public health reformers push the Hospital Service to partner with some enterprising chemists

Throughout the early 20th century, a number of private organizations lobbied the US government to become more involved in public health. These groups included labor unions, life insurance companies, social workers, and philanthropic foundations. Several of their campaigns boiled down to advocating a reorganization of existing programs from a divisional organization structure to a functional organization structure. It’s not clear to me this was really a great idea, but it seems like the public health advocates really wanted the government to spend more federal dollars on health overall, and the reorganization demand was a problematic political tactic that allowed them to claim they were seeking efficiencies, while inadvertently alienating the existing civil service.

The Hospital Service was defensive when it came to these possible reforms, as they feared they might be subsumed then eliminated inside some larger department. However, they too wanted some reforms made. It seems they were particularly upset about their poor job security and compensation. These compensation problems stemmed from federal rules that allowed medical doctors to receive federal commissions, but not scientists. To improve their compensation, leaders of the Hospital Service were open to forming political coalitions with reformers, so long as they retained their independence and won pay increases.

These reform campaigns set the stage for Senator Joseph E. Ransdell of Louisiana to partner with members of the American Chemical Society seeking to establish a new research institute for the study of “physiological chemistry.” The ACS members were interested in establishing an institute modeled on Rockefeller University (then, Rockefeller Institute), providing long-term support for basic research from a private endowment to understand the chemical basis of human disease.

After failing for nearly a decade to raise private funds, the ACS members were convinced by Ransdell that the US Government would be a worthy patron. Together, ACS members and Randsell collaborated to develop a proposal for a federal research institute that grew into the National Institute of Health (singular at first!).

In a funny anecdote, it appears Ransdell chose the name at the last minute, crossing out a previous name in the bill text and replacing it with NIH.

Ransdell and the chemists ran through the District of Columbia trying to gather support for their new proposal. After much effort, they received a luke-warm endorsement from the Hospital Service on the grounds that a bill for the new institute also included their desired pay increases. From personal correspondence of Hospital Service leaders, it doesn’t seem like they were all the favorable to the new institute, but really needed political help in the Senate.

In particular, the head of the Hygienic Laboratory viewed a new NIH-like institution as a competitor to his own existing efforts, and he believed it would be impossible to scale a research institution beyond the scope of the Hygienic Laboratory. It strikes me that fear of hypergrowth, and a failure to imagine large scale operation are a common failure mode within otherwise productive organizations like the Hygienic Laboratory.

How did they convince the public?

It took Ransdell and the ACS members 4 years and 2 US presidents to finally pass their NIH legislation. Harden provides an incredibly detailed account of the process. As expected, opposition to increased federal spending was the primary obstruction to the creation of the NIH, but idiosyncratic outcomes and the fickleness of individual legislative personalities also played a role in the lengthy road to acceptance.

The arguments put forward by Ransdell and supporters contained many familiar points. They emphasized the efficiency of preventative treatment for disease, the necessity of basic science for developing new medicines, and they leaned on past successes of federally funded basic research like the creation of a vaccine for Rocky Mountain Fever.

In addition to these familiar arguments, I’ll posit that three additional factors contributed to the NIH’s success:

Flexibility in the face of political reality

The 1928 influenza pandemic provided political momentum and a demand for action

Biomedical science had just entered a phase of exponential growth — successful exemplars were easy to find

Downsizing the ask

NIH proponents’ requested appropriation was based on cost estimates produced by the ACS for their envisioned institute — $10M over five years (~$150M inflation adjusted to 2020). Several Senators viewed this appropriation as exorbitant at a time when the US Government was much smaller in absolute terms than in the modern era (federal net outlays in 1929: $3.1B). After back and forth with the Andrew Mellon’s Treasury Department (yes, that Andrew Mellon), the initial appropriation was dramatically scaled back to $750,000.

While disappointed, Ransdell and supporters were willing to accept a small initial appropriation in exchange for creating the framework for federally funded biomedical research. They felt confident that future legislation would increase the allocation, and that the institution would become a valued part of American life. In these hopes, they proved prescient.

This willingness to scale ambition to political reality seems essential to establishing an inherently high risk endeavor like the NIH. Risk tolerance tends to increase when the downside is well bounded.

A desire for action in the face of tragedy

The contemporary epidemiological context no doubt also played a role. The winter of 1928-1929 saw the deadliest influenza pandemic since the pandemic of 1918. This crisis was entirely new to me, and seems to have faded from the broad public consciousness.

Both President Calvin Coolidge and members of Congress were more receptive to proposals for increased federal expenditures on healthcare and health research in the wake of the proximal tragedy. Coolidge himself vetoed an earlier public health reform bill, but his attitude warmed considerably following the pandemic such that he became one of the stronger political supporters of the legislation.

Coolidge’s reversal stands out to me as a positive example of how local context can influence long-term public policy making. We have an almost perfect counter-factual to consider what would have happened in the absence of the influenza outbreak. The bill had been before Congress already just a year prior, a similar bill had already passed and been vetoed, and yet with few if any changes, the NIH was able to win support once an acute event highlighted the importance of such an institution for long-term health of the public.

Exponential growth in biomedical capability

A key component of Ransdell’s presentation was a set of vignettes highlighting biomedical research advances with everyday impact.

In one portion of the presentation, Ransdell showed short microscopy film of motile cells in a culture dish taken by scientists at Rockefeller in Albert H Ebeling’s group during the hearings. These movies are so entrancing that many scientists (myself included) still work on understanding the biology on display today. I found this aspect of the argument endearing, and wanted to dig a little deeper than Harden’s coverage.

I found what appears to be the exact exchange captured here:

The cause of such diseases as nephritis, arteriosclerosis, cancer [..] must be discovered. [..] This cannot be brought without great advances in the knowledge of fundamental properties of cells. … This is a culture which has been placed in a suitable medium, and is functioning just as it did in a small embryo. […] Now what you are going to see going on before you is a process which in the incubator under the microscope covers a period of 24 hours and you are seeing in 15 or 20 seconds.

(I tried to find the original Ebeling film to no avail. The Wellcome recently restored some microscopy films from the same period, and I imagine the Ebeling film may have looked similar.)

The Rockefeller scientists explained that even though cell culture is artificial and a bit fanciful, these model systems had allowed them to develop a production system for Vaccinia vaccines.

This example is almost a perfect encapsulation of modern biomedical research. The scientists began their study by asking a simple question: What do animal cells need to survive? Can we provide everything a cell needs outside the body? They followed this conclusion through a series of experiments to find the proper culture conditions that allow for ex vivo cell cultures. Though unanticipated at the outset of research, these culture platforms proved useful in later studies of a virulent infectious disease and the production of treatment.

Exploring a fundamental question yielded an unexpected, unpredictable practical benefit.

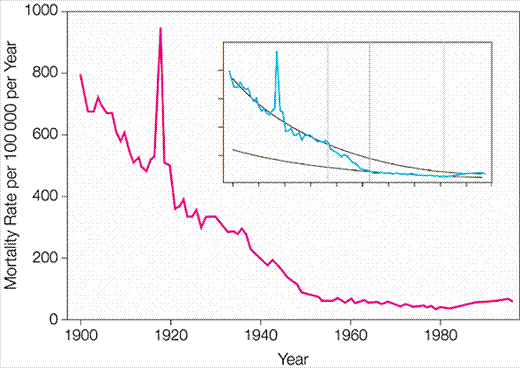

While this is only one such example, Ransdell’s presentation took place in the midst of long awaited biomedical advances that were making impacts on the lives of everyday Americans. Germ theory provided a framework for understanding and preventing infectious disease, to astonishing effect. Deaths from infectious disease were cut roughly in half (!) between 1900 and 1920 (see a Figure from Armstrong et. al. 1999, JAMA below).

Vaccines had been produced for several, previously ravaging diseases. The Hospital Service itself had identified the source of pellagra as a dietary deficiency, and identified common foodstuffs to prevent it. Just months later, penicillin would be discovered. Ransdell had examples abound of biomedical success and the benefits of research investment, many of which were apparent without being named.

This context of rapid, geometric decay in mortality from disease seems essential to achieving broad public support for a high risk research enterprise.

Acceptance, Passage, and Divisional Structure

Ransdell’s arguments were eventually accepted by both Houses of Congress and signed into law under Herbert Hoover, a rare excited about the application of scientific methods to all aspects of the public sphere (see Hoover: An Extraordinary Life).

Initially, the NIH was only a singular institute in a small building in the District of Columbia, almost exclusively focused on intramural research. It was not until the passage of the National Cancer Institute Act in 1937 that the NIH broadly adopted the practice of extramural research grants. Today, extramural grants to researchers at universities and private institutes makes up ~90% of the NIH budget. The NIH also settled into a “divisional” organizational structure in 1937, where divisions were defined by human diseases (a few exceptions exist in more modern times, the functionally focused National Center for Bio-Informatics being the most prominent).

Harden’s history ends in 1937, but the history of the NIH only blossoms later on. I look forward to exploring the decisions that led to the current system and possible mechanisms for improvement based on other successful funding agencies, like HHMI.

Are there other organizational structures or funding models that could help improve our rate of discovery?